Guest post by Marielle Lovecchio. This post is part of the Every Hour Counts STEM Connections series.

Last month, our Nashville-based trio made the trek to New York City with a specific aim in mind: to figure out how ExpandED Schools creates opportunities for students to engage in high-quality science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) learning after school, specifically through partnerships with formal (school day) and community (out-of-school) educators. We had all seen our share of one-off STEM activities, such as the infamous slime project, and were interested to see how collaboration between educators could lead to deeper STEM engagement. We wanted to learn how to help our students in Nashville’s expanded learning system, the Nashville After Zone Alliance (NAZA), reimagine their idea of what’s possible through the application of STEM.

Enter our guide, Adam Torres, the program director of the Morningside Center’s PAZ elementary afterschool program at PS 214. Torres’ passion for his work was evident from the moment we met; he easily transitioned from discussing pedagogy with us to fostering relationships with school administrators and students alike as he led us to the cafeteria, where a group of fourth grade students were about to begin their weekly STEM activity. Our NAZA team was full of anticipation to see the STEM exploration in action. Ms. Bishop, a teacher from PS 214, kicked off the session by introducing the goal of that day’s investigation and showing the students the various tools that would be at their disposal. Then Ms. Costello and Ms. Galloway, two community educators, reminded the students of the vocabulary and concepts they learned over the past few weeks to prepare them for the inquiry-based investigation.

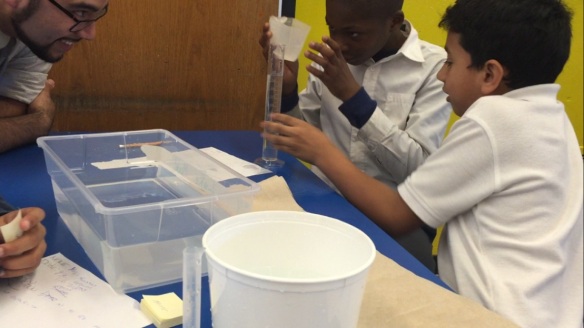

Torres works alongside a group of students in PS 214’s PAZ elementary afterschool program to help the students make the most meaning out of a STEM activity through co-inquiry.

As soon as the staff said “go,” the students began discussing as a team which group member would have what role (e.g. recorder, measurer, or presenter). They came alive as they made their predictions and investigated the most precise solution to their challenge: how many milliliters will it take to fill up your lake to capacity? Each group’s “lake” was a medium-sized plastic container that indicated the level of its capacity with masking tape. The educators checked in with each group to ask them questions and help them move smoothly through the investigation, but ultimately the students were in the driver seat. As our team moved around the space, we heard students utilizing their new vocabulary to talk with their group about what they were doing. The challenge captivated the students’ attention, and the student-driven exploration led to high levels of interaction and engagement.

So how did these educators create an environment where this kind of exploration was possible?

From what we saw, the formal and community educators shared equitably in the co-facilitation of the activities, and there was clearly a good deal of advance co-planning to ensure that the flow of the activity was smooth. There also appeared to be several other crucial pieces in place prior to our visit.

We saw evidence that the educators had sparked their students’ interest in previous sessions on the topic of liquid volume by asking students what they knew about water, what a drought was, and why water was important. That spark was stoked by an introduction to new vocabulary and tools that would eventually help students solve the challenge.

As we reflected on the site visit, we wondered what really made the students care about this activity. Was it the fact that it was presented as a challenge? The possibility that one group could finish the work more quickly than another group? Or that one group could ultimately be the most precise? Any of these could have been the reason, but it’s likely that the high level of student engagement derived from another source: the students were challenged to “save the lake” by measuring the lake’s capacity so that animals could survive.

These elements together make a formula for students enjoying and engaging in STEM expanded learning opportunities that we can replicate. For fun, engaging STEM, formal and community educators should collaborate to spark students’ interest, preview STEM vocabulary and concepts, connect those concepts to students’ real-world context, and present students with a challenge where they have the power to help change what’s possible with their STEM skills.

This holistic approach is exactly what we needed to see to envision the end goal for our Frontiers in Urban Science Exploration (FUSE) 3.0 work in Nashville. We aspire for our FUSE work to positively impact students’ interest, engagement, and motivation in STEM, and we are banking on the fact that our expanded learning system is uniquely positioned to do just that.

We are grateful to our hosts at ExpandED Schools for making our visit possible. It is hard to believe that a one-hour site visit turned out to be the missing puzzle piece in a six-month planning process. We are now moving full steam ahead with a clear vision for STEM expanded learning opportunities in Nashville and have ExpandED Schools, Morningside Sanctuary, and PS 214 to thank!

Marielle Lovecchio is a Zone Director with the Nashville After Zone Alliance (NAZA), a nationally-recognized system of free, high-quality afterschool programs that provide academic support and new creative outlets for Metro Nashville Public Schools’ middle school students. NAZA is one of seven communities expanding informal STEM education for their students through the Frontiers in Urban Science Exploration (FUSE) project. The project, supported by the Noyce Foundation, aims to scale access to high-quality STEM learning for kids in out-of-school time programs.